Iceland has experienced over 20,000 moderate earthquakes since the ongoing swarm began on February 24, accompanied by increasing signs of magma movement beneath the surface. Although all but two of the quakes have been below 5.0 on the Richter scale, the nigh-continuous stream of tremors signals the possibility of an imminent eruption from one or more of the island nation’s volcanoes.

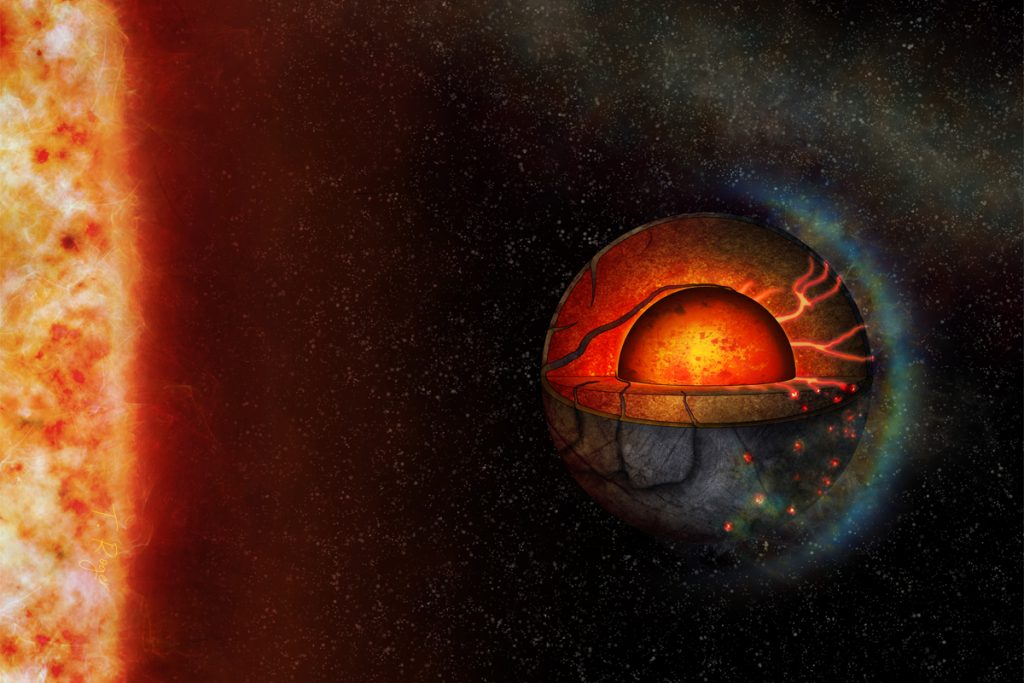

Although Reykjanes Peninsula, the region of Iceland where the ongoing earthquake swarm is occurring, is only 32 km (20 miles) from the country’s capital of Reykjavik, no damage or injuries have been reported so far. Iceland is one of the few portions of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge that extends above water, meaning the island straddles the rift between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates, two major geological features that are spreading apart at a rate of 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) per year; The island itself was formed by the upwelling from the Iceland hotspot, a volcanic region fed by the underlying mantle deep within the earth. Because of these factors, Iceland is no stranger to seismic and volcanic activity, the latter of which is a source of geothermal power and a major tourist draw.

Despite Icelanders’ familiarity with earthquakes, the frequency of tremors in this ongoing swarm has some residents “waking up with an earthquake, others [going] to sleep with an earthquake,” according to Thorvaldur Thordarson, a professor of volcanology at the University of Iceland. Thordarson also added that despite the increase in seismic activity, there’s “nothing to worry about.”

Previous seismic swarms have preceded volcanic eruptions in the Island’s southern regions, according to the Icelandic Meteorological Office (IMO), and the tremors are most likely being caused by magma movement at the boundary where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates meet, a subterranean flow that could erupt through the five active volcanoes that dot the Reykjanes Peninsula.

An eruption from Iceland’s southern volcanoes pose no immediate danger, and are right on cue for the region’s 800-year cycle of seismic pulses, the last of which occurred between the 11th and 13th centuries. The release would be expected to be far less violent than the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull that sent a 9 km (5 mile) column of ash into the atmosphere that forced local evacuations and disrupted air traffic over Europe for six days.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.