“Time moves in one direction, memory in another.” ~ William Gibson

While physicists and philosophers have been trying to unravel the mystery of time itself for, well, a long time now, the latter half of Gibson’s quote is well worth looking at: if our perception of time—a or more importantly, our memory of the sequence of events—is what keeps everything from happening at once, is there a part of our brain that puts those memories in order, so that we don’t remember everything we’ve experienced as having happened all at once, or wildly out of order?

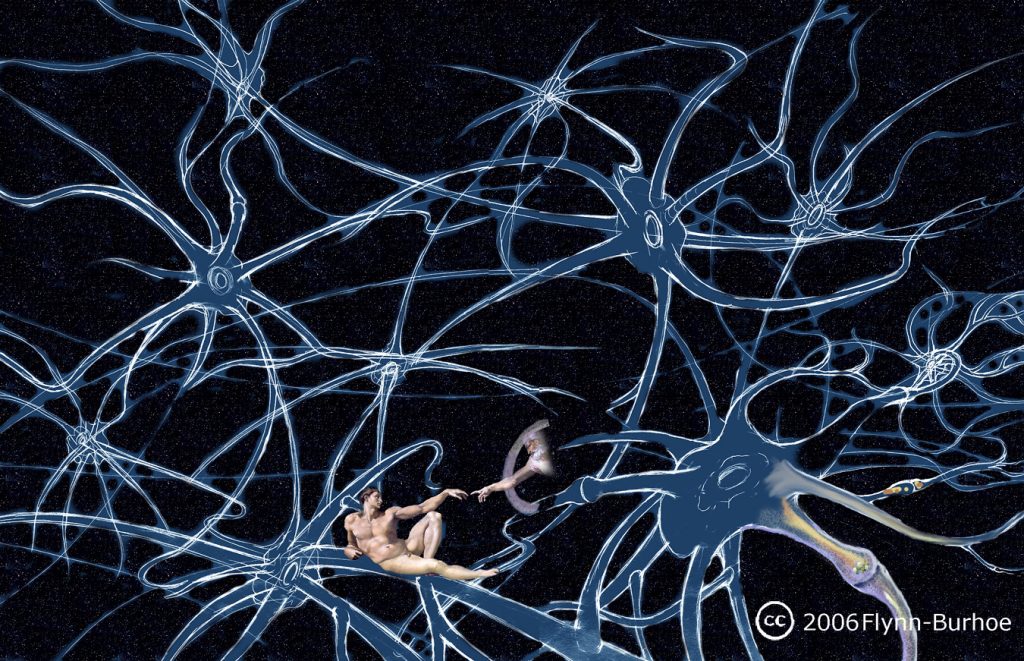

Evidence for the existence of sequence-tracking “time cells” that would record our memories in order had been found in previous studies involving rats, but little was known in regards to how the human brain goes about encoding episodic memories. To that end, neuroscientists with France’s Brain and Cognition Research Center (CerCo) monitored the electrical activity in the brains of 15 epilepsy patients to see if they could uncover any neurological activity that would suggest that the brain was encoding its memories in order.

The researchers used diagnostic microelectrodes that had been previously installed in the hippocampus of each of the subjects, implants originally used to help locate the source of the patients’ seizures. The hippocampus is a pair of structures, one for each hemisphere of the brain, located in the brain’s temporal lobes, and is responsible for the consolidation of information from short-term memory to long-term memory, and also for our spatial memory that enables navigation.

“Creating episodic memories requires linking together distinct events of an experience with temporal fidelity,” according to the study text.

“Given the importance of the hippocampus in sequence order learning and temporal order judgments, we tested whether human hippocampal neurons represented temporal information while participants learned the order of a sequence of items.”

While the subjects learned the order of the items presented, the research team monitored the electrical activity in their hippocampi, with a focus on the times when the images were shown, the pauses between presentations, and the instances when the subjects were asked to recall the next image when the sequence was replayed.

The researchers found that while some of the neurons were actively engaged in memorizing or recalling the sequence of images, there were others that were still active when the subjects were not being presented with the images, suggesting that they were active in encoding the flow of time, even when no new stimulus was being experienced, “neurons whose activity is modulated by temporal context within a well-defined time window,” according to the study.

“Time cells were observed to fire at successive moments in these blank periods,” the study text continues. “Temporal modulation during these gap periods could not have been driven by external events; rather they appear to represent an evolving temporal signal as a result of changes in the patients’ experience during this time of waiting.”

The researchers also refer to the time cells as “multi-dimensional”, meaning that they appear to be capable of encoding information in relation not only to time but are also capable of responding to different kinds of sensory information, allowing them to not only record the ‘when’ of an experience, but also other aspects like ‘what’ and ‘where’, putting together a cohesive narrative out of what would otherwise be an uncoordinated jumble of sensory inputs.

“The phenomenon of subjective ‘mental time travel’ is a cornerstone of episodic memory,” according to the study. “Central to our experience of reliving the past is our ability to vividly recall specific events that occurred at a specific place and in a specific temporal order… Our results provide further evidence that human hippocampal neurons represent the flow of time in an experience.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.