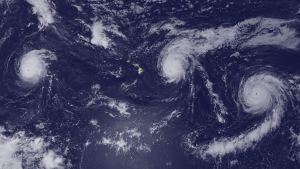

A proposal to amend the current five-level scale used to measure the severity of hurricanes to include a sixth category for the most powerful of tropical cyclones has been put forward, as a method of improving the classification—and thus the communication of—the destructiveness of a given storm, especially as we face the rise of increasingly powerful hurricanes fueled by global warming.

The hurricane classification system in use today, the Saffir-Simpson scale, was introduced in 1973, and divides the severity of individual storms into five different categories according to their wind speeds, starting at 33-42 meters per second (74-95 mph; 119-253 km/h; or 64-82 knots) for a category 1 storm, and topping out at winds greater than 70 meters per second (157 mph; 252 km/h; or 137 knots) for a category 5.

But with the increase in both the frequency and severity of storms being generated by a warming climate, the usefulness of the Saffir-Simpson scale—at least the open-endedness of the category 5 segment—has been called into question, most recently by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory senior scientist Michael F. Wehner, and University of Wisconsin–Madison’s James P. Kossin. Wehner and Kossin propose adding an 86 meter-per-second (192 mph; 309 km/h; or 167 knot) upper limit to the scale’s fifth category, and adding a sixth level of storm severity to the list for winds speeds above that threshold.

Under the current scale, 197 hurricanes have been designated as category 5 between 1980 and 2021, with five of them reaching an intensity that would qualify them to fall into Wehner and Kossin’s proposed sixth: Typhoon Haiyan in 2013; Hurricane Patricia in 2015; Typhoon Meranti in 2016; Typhoon Goni in 2020; and Typhoon Surigae in 2021. Note that all five of these storms have occurred within the last eleven years.

Of those five, 2015’s Hurricane Patricia had the most powerful sustained winds, clocking in at 215 mph (95 m/s; 345 km/h; 185 knots)—36 km/s per second above the 309 km/s proposed for category 6’s lower limit.

“That’s kind of incomprehensible,” remarked Wehner “That’s faster than a racing car in a straightaway. It’s a new and dangerous world.”

While lumping different hurricanes of varying severity into individual categories may at first seem to be arbitrary, it can be a useful tool in communicating what to expect from a given storm to the public: for instance, an individual might have a house built to withstand a category 4 storm, so they might not need to take any additional measures if a category 3 is in the forecast; conversely, if the individual is told that a category 5 is on the way, they will know to batten down the hatches, so to speak.

However, despite the destructiveness of a strong hurricane’s wind speeds, this metric does not properly encapsulate the other hazards involved with these extreme storms.

“The Saffir-Simpson scale is not all that good for warning the public of the impending danger of a storm,” Wehner added, regarding the advances made in regards to predicting the destructive potential of hurricanes in the half-century since the system was introduced: although wind speeds were the only metric available at the time, storm surges, flooding and rip tides have proven to be their far more destructive elements

“Thirty years ago, that’s basically all we could tell you about a hurricane, is how strong it was right now,” National Hurricane Center director Mike Brennan said during a recent public meeting, in regards to judging a hurricane by winds speeds alone.

“We couldn’t really tell you much about where it was going to go, or how strong it was going to be, or what the hazards were going to look like. We can tell people a lot more than that now.”

Brennan said that the NHC has no plans to revise the Saffir-Simpson scale; rather, the agency is currently trying “to not emphasize the scale very much,” due to the limited use of wind speed as a metric.

“I don’t see the value in it at this time,” according to Mark Bourassa, a meteorologist at Florida State University’s Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. “There are other issues that could be better addressed, like the spatial extent of the storm and storm surge, that would convey more useful information [and] help with emergency management as well as individual people’s decisions.”

“What the Saffir-Simpson scale is good for is quantifying, showing, that the most intense storms are becoming more intense because of climate change,” Wehner explained. “It’s not like it used to be.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

“storm surges, flooding, and rip tides” … These are all water issues that will grow (exponentially??) more violent with the progression of sea level rise in this 21st century. If so, the way forward may be to combine the Saffir-Simpson scale with fractions (or other math measures) that represent increasing sea level rise.

I posed this question today to U Penn climatology professor Michael E. Mann, PhD, and he said it’s hard to do that, and referred me to his most recent PNAS essay on that subject: https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2322597121