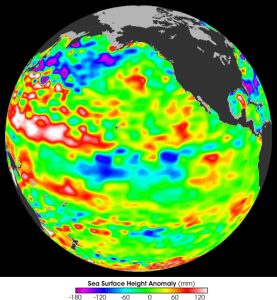

An unexpected mystery has appeared at the equator in the Atlantic Ocean, in the form of a sudden cooling trend in the surface waters, despite the ongoing record-breaking warming of the ocean surface and a lack of the conditions that would typically be required for La Niña-like conditions to form there—a situation that could affect how this year’s hurricane season could unfold in the Atlantic.

Although it isn’t as well known and lacks the impact of its Pacific counterpart, the Atlantic Niño/Niña, or the Atlantic Equatorial mode, is a cyclical phenomenon that waxes and wanes in accordance to the winds found at the equatorial Atlantic: every few years the trade winds increase, pushing the warm water at the ocean’s surface to the south, in turn allowing cooler water from deeper in the ocean to well to the surface to replace the displaced surface water.

This mode is called, as one might expect, Atlantic Niña; conversely, when the trade winds weaken and allow warm water to build up at the equator, the phenomenon is referred to as Atlantic Niño.

While the current formation of Niña conditions in the Atlantic isn’t out of the ordinary, the circumstances regarding its appearance is confounding scientists for two reasons: first off, the sudden onset of the current cooling conditions in the mid-Atlantic is the most rapid seen since recording of the phenomenon started in 1982; and secondly, the trade winds in the region do not have the strength to be displacing enough surface water to account for the recent cooling effect. In fact, this onset of Atlantic Niña conditions coincided with a weakening trend of the strength of the trade winds.

Additionally, the appearance of Atlantic Niña doesn’t typically coincide with its La Niña counterpart in the Pacific, of which is given a 66 percent chance of forming between September and November in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) most recent forecast.

Although its influence is more subtle, Atlantic Niña can counteract some of the effect that La Niña has on the formation of hurricanes in the Atlantic: while the cooling of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) band in the Pacific tends to decrease high-altitude wind shear to the east over the Atlantic, allowing tropical cyclones to reach higher into the atmosphere and, in turn, gain more strength, the cool waters associated with Atlantic Niña conditions rob the region where tropical storms form of their energy, resulting in weaker storms. Atlantic Niña conditions can also weaken the winds over the Pacific that generate La Niña conditions there, potentially forestalling the formation of such conditions to begin with.

This is important in regards to the record number of predicted number of storms for this year’s Atlantic hurricane season issued by NOAA in May, as the agency’s model was dependent on temperatures in the mid-Atlantic remaining warm throughout the remainder of the season; instead, the cooling conditions may cause the actual number of serious storms to fall short of NOAA’s prediction.

Atlantic Niña conditions can also affect rainfall on either side of the Atlantic, causing dry conditions over Africa’s Sahel region along the southern edge of the Sahara Desert; conversely, it can bring increased rainfall to the regions surrounding the Gulf of Guinea.

In the meantime, climatologists are trying to figure out what prompted this season’s Atlantic Niña, both in terms of its rapid onset and counterintuitive formation.

“We are still scratching our heads as to what’s actually happening,” remarked Michael McPhaden, a senior scientist with NOAA who is the Director of NOAA’s Global Tropical Moored Buoy Array (GTMBA) project. “It could be some transient feature that has developed from processes that we don’t quite understand.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.