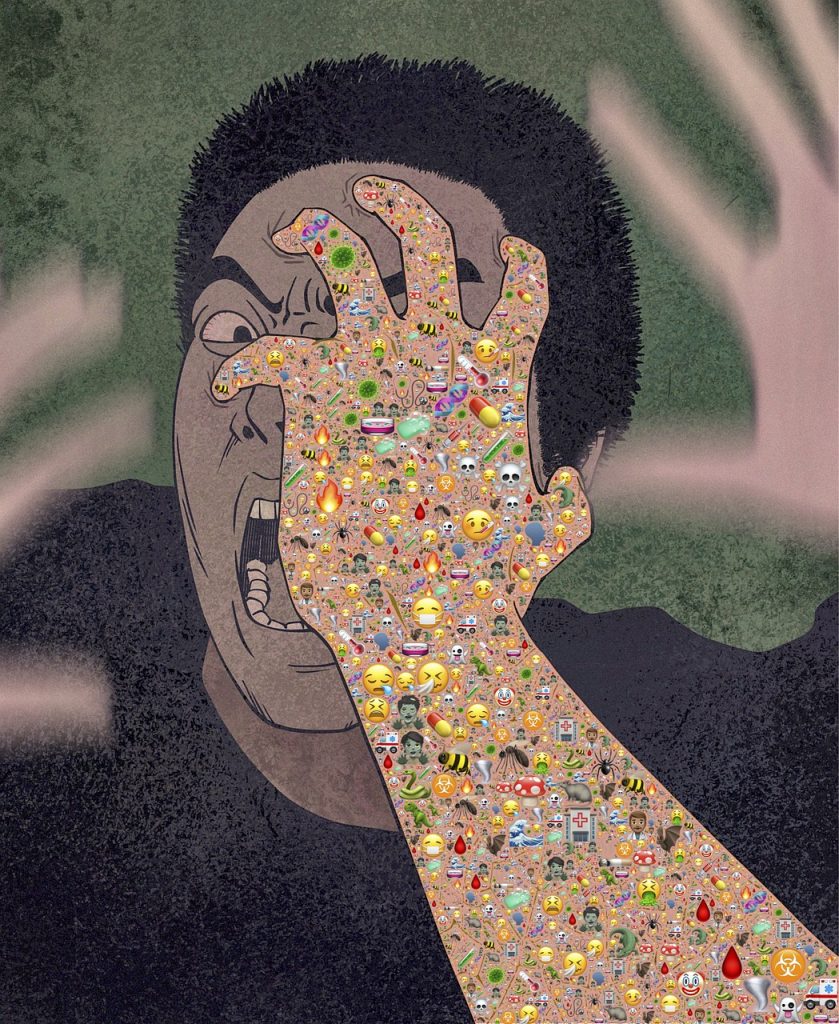

A clinic in Amsterdam has been helping people with crippling fears overcome their phobias by hacking their neurochemistry, with the dose of a single pill being all that is necessary to allow many of the clients of the Kindt Clinic to reclaim their lives from irrational fears that can hamper, or sometimes even cripple, their daily lives. The program boasts an 85 percent success rate, having successfully treated 493 individuals out of 580 clients over the last half-decade, permanently banishing a range of phobias spanning 36 different fears.

Founded by University of Amsterdam professor and clinical psychologist Merel Kindt, the Kindt Clinic uses what they call the Memrec Method, a process that involves exposing the client to their fear, and then giving them a pill to cure it. Kindt based her process on an experiment conducted in 1999 at Canada’s McGill University: in the experiment neuroscientist Karim Nader conditioned lab mice to associate a high-pitched beep with an electric shock, so that whenever the beep sounded alone, the mice would react with fear, anticipating the electric shock. He then administered anisomycin to the mice, while replaying the same beep. While typically used as an antibiotic, anisomycin is also known to be a protein-synthesis inhibitor, preventing the formation of long-term memories. Following the treatment, the mice began to disregard the beep, indicating that their fear of it was gone.

The theory behind what was happening is that the process of “memory reconsolidation”, the strengthening of one’s synapses during the recall of a memory, is being interrupted by the presence of the anisomycin, allowing a new memory to overwrite it. When the brain forms a new memory, our synapses, the spaces between the individual neurons, write themselves, chemically recording a pattern that corresponds to the new memory. When the memory is recalled it is consolidated, in that it is made permanent, forming a long-term memory. And until recently, scientists assumed that these permanent pathways couldn’t be re-written.

In 2015 Kindt conducted an experiment involving 15 volunteers that suffered from arachnophobia: the subjects were administered , while being instructed to contemplate touching a spider, something they wouldn’t ordinarily be able to force themselves to do. In all 15 cases, the subjects were able to successfully, and more confidently, touch a live tarantula. The effect also did not diminish, with the subjects still being able to approach spiders a year after their treatment. Since then, Kindt has opened Kindt Clinics to facilitate the Memrec Method, and has helped nearly 500 people overcome their fears.

“First [we] trigger the fear memory by exposing people to a situation or stimulus that they fear,” Kindt describes of the clinic’s current method. She then adds a new element to the experience, for instance challenging a patient afraid of heights to not close their eyes while elevated high above the ground. “This is a signal to the brain to update the memory,” she says. “The memory trace is temporarily in a destabilized state.

The client is then administered a dose of propranolol, a drug that has been used since the 1960s to treat heart conditions and anxiety. Typically, the fear memory would be re-saved in the experiencer’s brain while they sleep that night, but the beta-blocker interrupts that process, allowing the client to form a long-term memory of the previous day’s experience without attaching the older trauma memory to it.

Application of the Memrec Method is better suited to treating fears that can occur in everyday circumstances, such as fears of needles, heights, spiders or small spaces, since the client needs to be exposed to what they fear for the treatment to work; more abstract fears, such as that of death, or ones that can’t be recreated in a practical or safe manner, such as combat-related PTSD, aren’t well suited to the method, and will require more development before they can be incorporated into the program. Kindt’s process is also not meant to be used on everyday, rational fears.

“The cure is only meant to cure irrational fears, not necessary fears,” Kindt explains, but admits that it can be hard to tell the difference between the two at times: being afraid of bears while in the middle of a bustling city is irrational; conversely, being afraid while a bear is actually chasing you is very necessary. “It’s been kind of a process of re-learning when my fear is appropriate and when it’s not,” Kindt adds. “I definitely have felt a reduction in the irrational panic, I think.”

The strikingly successful treatment of two of Kindt’s clients is featured in BE AFRAID: The Science of Fear, an episode of the CBC’s The Nature of Things.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.