A Phase I clinical trial of an experimental anticancer drug has begun, using a specialized virus designed to selectively attack the cells that make up the targeted tumor. A separate cancer study has also produced the unprecedented—yet very welcome—outcome of successfully treating the cancer that was present in all of the subjects that participated.

The virus-based treatment, currently undergoing Phase I trials to determine its safety and tolerability when used in a human patient, is called CF33-hNIS, or Vaxinia, and employs what is called an “oncolytic virus” as the mechanism meant to attack and eliminate cancer cells. This virus being used is a genetically-modified smallpox virus that has proven to be effective against a wide variety of cancers in lab animals, and if this drug passes its trials and regulatory hurdles it is intended to do the same for human patients.

“The particular importance of CF33/ Vaxinia is that this virus is designed to target all types of cancers,” explains Dr. Yuman Fong, the chair of the Department of Surgery at City of Hope, where the Phase I trials are being conducted. “It is one of the first of a new generation of therapeutic viruses that would be much more potent than prior viruses, and it is potentially more selective for cancer while able to spare normal tissues.”

The use of oncolytic viruses has been of interest to medical science for more than a century, ever since a link between the regression of certain cancers and viral infections were noticed; virotherapy, the deliberate infection of the subject with a virus, also began as a potential cancer treatment in the mid-twentieth century.

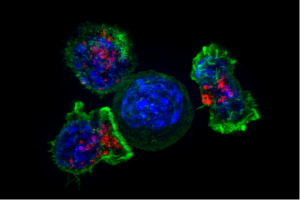

The mechanism behind such therapies is two-fold: the viruses selectively infect and kill the targeted tumor cells, an effect produced by tailoring the virus to only latch on to receptors that are only found on the surface of the cancer cells.

The second method lies in the virus’ act of killing the tumor cells: when the cell is destroyed it releases antigens specific to the tumor cells, providing a chemical signal that overcomes the immunosuppressive effect caused by the cancer cells that prevents the body’s immune system from attacking the rogue cells to begin with; in this way, the oncolytic virus prompts the immune system to target and attack the tumor itself.

A separate study using a different treatment against the rectal cancer of a small group of subjects had the fortune of being successful in putting the cancer of each and every one of its subjects into remission, an unexpected result that brought about “a lot of happy tears” according to one of the study paper’s co-authors.

“I believe this is the first time this has happened in the history of cancer,” exclaimed another co-author, Dr. Luis A. Diaz Jr. of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

The treatment involved a monoclonal antibody called Dostarlimab, a drug already cleared for use against endometrial cancer. It works by blocking the production of immune checkpoint proteins, molecules that prevent the immune system from attacking the body’s cells indiscriminately, including cancer cells that make use of these molecular blocks.

The study itself was small, with only 12 participants with a specific type of localized rectal cancer that held a mutation that prevents cells from repairing damage to their DNA, a mutation that occurs in four percent of all types of cancer, and an effect that Dostarlimab also addresses. The subjects were given treatments once every three weeks for six months, and were expected to receive the standard treatment for rectal cancer—chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgery—after the study had concluded.

But instead, a battery of MRI and PET scans, endoscopy, and biopsy examinations of every one of the study’s participants showed that their cancers had gone into remission, a “clinical complete response,” according to the study paper, meaning that none of the patients needed to face the life-altering treatments that are typically used to treat rectal cancer. And even two years after the study the participants remained cancer-free.

“At the time of this report, no patients had received chemoradiotherapy or undergone surgery, and no cases of progression or recurrence had been reported during follow-up (range, 6 to 25 months),” according to the study paper.

The study authors caution that there is more work to be done to determine if this form of cancer treatment is both safe and effective for rectal cancer patients, considering the study’s small group size and the relatively short amount of time since the study’s conclusion: it’s very possible that, in time, the patients’ cancers might return, and the universal remission seen across the group may have been a fluke that won’t be seen in a larger study.

“Whether the results of this small study … will be generalizable to a broader population of patients with rectal cancer is… not known,” comments oncologist Hanna K. Sanoff from the University of North Carolina.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.