Researchers from Canada and Denmark have found that a prolonged heat wave in the waters of the Pacific Ocean nicknamed the Blob have disrupted the balance in the microscopic marine life that lives in the region, threatening the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The researchers also warn that more extreme events such as this should be expected as global temperatures continue to rise.

“Marine heatwaves are one of the big challenges of climate change,” explains the University of Southern Denmark’s Dr. Sachia Traving, the study’s lead author. “Knowing how they affect microbes – some of the smallest but most abundant organisms on earth – will help us understand how heatwaves will impact life in our future oceans.”

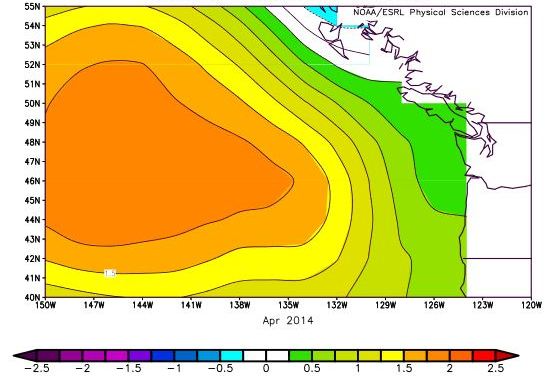

First detected in 2013, the Blob was a marine heat wave that persisted through to 2016 that saw sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean off of the west coast of North America rise 2.5°C (4.5°F) above normal; in June 2014 the anomaly expanded across a stretch of ocean 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) across, reaching a depth of 90 meters (300 feet). The anomaly was caused by the local waters experiencing a lower rate of heat loss to the atmosphere, compounded by a lack of circulation in the upper layer of water; these two phenomena were caused by a slowdown of water currents in the Pacific that would ordinarily be driven by surface winds, and this effect was a result of the presence of a weather anomaly nicknamed the Ridiculously Resilient Ridge, a region of static high pressure in the atmosphere that formed in the spring of 2014.

The prolonged heat wave brought about by the Blob affected the marine life in the region, especially microbes such as the phytoplankton that form the base of the food chain in the ocean; being photosynthesizing creatures, phytoplankton use sunlight to convert the carbon dioxide they consume to produce chemical energy that is stored in their bodies. Aside from being responsible for absorbing roughly thirty percent of human-based CO2 emissions, the carbon stored in the bodies of these (mostly) microscopic creatures is trapped in the organic matter left over when they die, sinking to the bottom of the ocean.

But the researchers found that during the time that the Blob was present, the affected waters saw a rise in the number of microbes that have evolved to specialize in thriving under nutrient-poor conditions, indicating that there was less phytoplankton present to provide food to the species that would usually consume them—a troubling development for the ocean’s role in processing atmospheric carbon dioxide, considering that the global warming-fueled conditions that provoked the formation of the Blob are not going away anytime soon.

“This ‘biological pump’ process is an important mechanism for buffering the impact of human activity on Earth’s climate,” according to study co-author Dr. Colleen Kellogg, a research scientist with Canada’s Hakai Institute. “The ocean is a huge global reservoir for atmospheric carbon dioxide. If marine heatwaves reduce the capacity for carbon dioxide to be absorbed into the ocean, then this shrinks this reservoir and leaves more of this greenhouse gas in the atmosphere.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.