Health authorities around the world are finally getting a clearer picture of the nature of the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 coronavirus, and there’s both good news and bad news: the good news is that this form of the virus is less likely to cause a case of the illness serious enough to land an infected patient in hospital. The bad news is that Omicron’s mutations allow it to readily evade prior immunity to COVID-19, and compared to its predecessors this strain spreads like wildfire: many regions are reporting a case-doubling time of a little over two days, meaning that the sheer volume of cases caused by Omicron’s rampant transmissibility has all but ensured that it will overwhelm hospitals.

As health authorities around the world continue to crunch the numbers, it appears that individuals infected by Omicron are about 50 percent less likely to be hospitalized than those hit with the Delta variant; however, Omicron’s “tsunami”-like ability to spread renders that bit of good news moot, with the strain’s two-day doubling time having already allowed it to eclipse Delta as the dominant variant in many countries by late December 2021. Although it is somewhat less likely to cause severe illness, the sheer volume of cases has caused a new surge of hospitalizations that are causing further strain on already overburdened health care systems around the world. As an example, COVID-19 cases in Florida jumped by 948 percent in the last two weeks of December, fueling a 40 percent surge in hospitalizations.

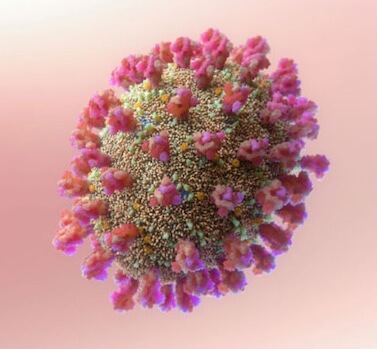

Omicron is a heavily-mutated SARS-CoV-2 variant, sporting a spike protein configuration that has changed enough to allow the virus to evade most COVID-related antibodies produced by the immune system, regardless of whether this immunity was acquired by infection or vaccination.

But part of Omicron’s ability to duck our immune systems is how these key antibodies fade from our system over the months following a vaccination; basically, the antibodies not only have trouble latching on to the new spike proteins, but there’s also typically not enough of them to be effective for when they do. To that end, booster shots have been found to improve an individual’s chances against being hospitalized dramatically, with one South African study showing that the third jab increased protection from being hospitalized with a severe case of COVID-19 from 63 to 85 percent.

The changes to Omicron that are behind its incompatibility with earlier antibodies also appear to affect the virus’ ability to infect key body tissues: compared to Delta, this variant has been found to spread 70 times faster in the bronchi—the air passages in the lungs—but at the same time it seems unable to penetrate as deeply into lung tissue as other forms of COVID. This later factor may be why there are fewer instances of Omicron-caused COVID-19 cases landing in hospital.

But now is not the time to slip into complacency, as the rampant spread of even a supposedly-milder form of COVID-19 can still present the risk of severe disease in immunocompromised individuals such as cancer patients, HIV-positive individuals and organ transplant recipients, groups that run a high risk of vaccinations failing to impart immunity to the coronavirus. And on a larger scale, overburdened health care systems have their ability to effectively care for all types of patients compromised, presenting a potential danger to everyone.

“You have a virus that looks like it might be less severe, at least from data we’ve gathered from South Africa, the UK and even some from preliminary data from here in the US,” according to National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Dr Anthony Fauci.

“It’s a very interesting, somewhat complicated issue… so many people are getting infected that the net amount, the total amount of people that will require hospitalization, might be up. We can’t be complacent in these reports. We’re still going to get a lot of hospitalizations.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.