Two major strains of the virus that causes the seasonal flu appear to have disappeared, an unintended positive effect of the measures taken over the last fifteen months to prevent the spread of the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. This is good news not only for those looking to avoid contracting the flu every year, but it also makes the job of those coming up with each season’s flu vaccine easier, and in turn making each season’s shot more reliable in its effectiveness.

Two major strains of the virus that causes the seasonal flu appear to have disappeared, an unintended positive effect of the measures taken over the last fifteen months to prevent the spread of the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. This is good news not only for those looking to avoid contracting the flu every year, but it also makes the job of those coming up with each season’s flu vaccine easier, and in turn making each season’s shot more reliable in its effectiveness.

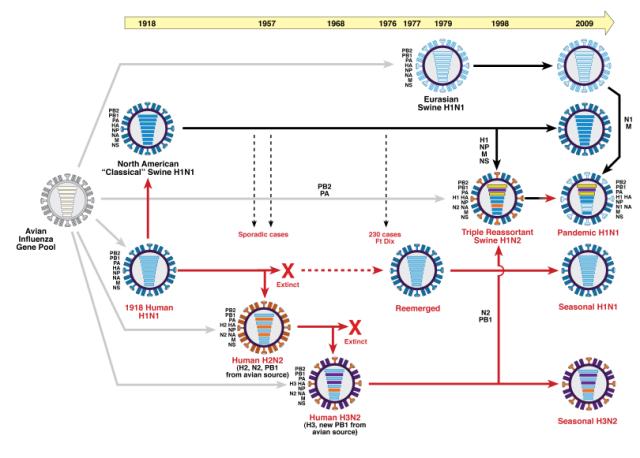

Two major strains of the influenza virus, called “clades” in virology lingo, appear to have disappeared: specifically, the influenza A H3N2 virus, also known as 3c3, and one of the two influenza B viruses—B/Yamagata—have failed to make an appearance in international databases used to monitor flu virus evolution in over a year, with March 2020 being the last time either of the two viruses were logged. This doesn’t necessarily mean that these clades have gone completely extinct, but may have had their spread dampened enough to have not made their presence known over the past 15 months.

Reported cases of the flu have also dropped dramatically during the pandemic: in an average year, the repository used by researchers and public health officials to monitor the evolution of influenza and coronaviruses, GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data) would receive the genetic sequences of about 20,000 flu viruses, but this year only 200 flu viruses were logged, with H3N2 and B/Yamagata being noticeably absent.

“I think it has a decent chance that it’s gone. But the world’s a big place,” said Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, referring to H3N2’s absence.

There are two key families that cause the flu in humans, influenza A and influenza B: H3N2, along with H1N1, are the two subgroups within the influenza A group that circulate amongst the human population; being zoonotic viruses—having originated in animals like birds—influenza A is also the more dangerous of the two families. While there are no subtypes within the influenza B group, it does consist of two lineages, known as B/Victoria and B/Yamagata.

Traditionally, only three of the four versions of the virus would be included in a given season’s flu shot, but in recent years it has been necessary to include all four, as mutation-driven diversity between the different groups has increased. H3N2 in particular has become increasingly divergent since 2012, making its inclusion in any given season a nail-biter of a choice for virologists, with the consequences for the wrong decision being felt in situations like the 2017-2018 flu season, where the incorrect countermeasures for that season’s flu resulted in the vaccine only being 25 percent effective.

“We work so hard to get quadrivalent vaccines… and now, if really Yamagata has disappeared, then actually trivalent [vaccine] would be okay again,” according to Ben Cowling, a flu expert at Hong Kong University.

Aside from the public having taken measures such as masking, hand-washing and social distancing to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, a major reduction in international travel may have played a big part in stifling these flu variants, according to Helen Branswell, a senior writer at STAT News specializing in infectious diseases.

The “flu moves from the Southern Hemisphere in their winter and our summer to the Northern Hemisphere when it’s our flu season,” Branswell explained in an interview with NPR. “And that just doesn’t seem to have been happening to the degree that it normally does. And as a consequence, there are just fewer of these viruses around.”

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

Thank you for this essay. As of 2024, US virologists at the CDC are still not finding the Yamagata strain and have reformulated the US influenza vaccine accordingly.

In a Canadian paperback book written by an emergency physician and a public health physician, The Flu Pandemic And You, with a foreword by the author Margaret Atwood, they make the excellent point that in the 21st century, with the increased prevalence of avian flu, anyone keeping a domestic bird flock (chickens, geese, turkeys, etc.) should get a flu shot each year, or as often as public health authorities recommend in your country. (Bird-to-human avian flu transmission is becoming more common.)

Their other advice (page 129): “Avoid unnecessary contact with domestic poultry and wild birds. Transmission occurs via close contact with them and their secretions and feces.”

On page 256 the authors state, “One of the active ingredients in Tamiflu, shikimic acid, is found mainly in the star anise plant, whose primary source is in China.” US grocers such as Bristol Farms, however, sell organic star anise in their spices section, so we could use star anise seed pods when making our own soups or broth at home.