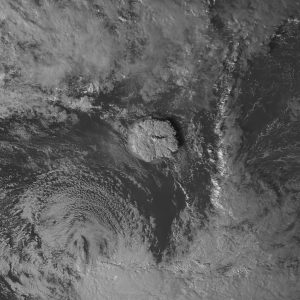

The explosive eruption of the Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai underwater volcano in January was the largest explosion on record—either man-made or natural, rivaled only by the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa—and the largest volcanic eruption since Mount Pinatubo’s 1991 eruption, making for an event that ejected a massive amount of material high into the atmosphere. However, scientists are concerned that instead of cooling the atmosphere as land-based volcanoes tend to do, the millions of tons of water blasted into the atmosphere by Hunga Tonga’s eruption might only add to the ever escalating problem of global warming.

Although the average land-based volcanic eruption typically releases a fair amount of carbon dioxide, the effect of this greenhouse gas is usually offset by the release of sulfur dioxide (SO2) high into the stratosphere, a compound that reflects incoming sunlight back into space; for instance, Mount Pinatubo’s 1991 eruption ejected 20 million tons of SO2 into the atmosphere, temporarily cooling the Earth’s average temperature by 0.7°C (1.3°F) for three years.

However, Hunga Tonga’s explosive eruption occurred entirely under water, meaning that in addition to the usual CO2 and SO2 ejected a massive amount of water was blasted into the atmosphere, estimated to be at least 50 million tons worth.

The presence of water in Hunga Tonga’s ejecta was discovered by a radiosonde launched high into the atmosphere over Fiji; the instruments on board this device, held aloft by a weather balloon, recorded an increase in the levels of water vapor between the altitudes of 19 and 28 kilometers (11.8 and 17.4 miles); the water plume was also detected by another radiosonde launched over the east coast of Australia.

Even two days after the eruption the water levels at those altitudes were 580 times higher than normal, despite enough time having elapsed for the vapor to have dissipated. The researchers estimate that over 50 billion kilograms (50 million metric tons) were launched into the atmosphere by Hunga Tonga; they also stated that this is a conservative estimate, with the real amount of H2O ejected being much higher.

This massive amount of vaporized water presents a problem when it comes to the issue of global warming: although the excess CO2 currently in the atmosphere is the main driver of global warming, it is water vapor, a far more potent greenhouse gas, that is what helps keep our planet’s temperature relatively stable and warm.

However, unlike CO2, the concentrations of which are what affects the Earth’s surface temperature, it’s the atmospheric temperature that dictates how much water is present in the atmosphere at any given time: as air warms it is able to hold increasing amounts of H2O. This creates a feedback loop: as increasing carbon concentrations turn up the heat the atmosphere can hold more water, in turn causing more warming, allowing the air to hold even more water, and so on.

Compounding the greenhouse gas problem is that the excess water ejected seems to have prevented a large amount of the sulfur dioxide that accompanied the eruption from reaching the stratosphere, where it could have been effective in reflecting a portion of the incoming sunlight back into space.

The true impact of this excess water having been released into the atmosphere remains to be seen, although at lower altitudes the vapor plume appears to have absorbed enough heat to deprive the upper portions of 2°C (3.6°F) worth of thermal energy. There is also the consolation that eruptions like Tunga Honga’s are relatively rare: most submarine eruptions take place deep within the ocean, with the water above absorbing the kenotic energy from the eruption. Conversely, the 2022 Tunga Honga eruption took place in shallow water, meaning there was very little mass in way to prevent its ejecta from being launched high into the atmosphere.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

The most powerful volcanic eruption in modern human history was the 1815 explosive eruption of Tambora in Indonesia, which was significantly more

powerful (4 to 10 times greater) than that of the better known Krakatoa. On the Volcanic Explositivity Index, Tambora was a definite VEI-7, Krakatoa a VEI-6.

Hunga Tonga was evaluated in May of this year as a VEI-6, less powerful than Tambora.