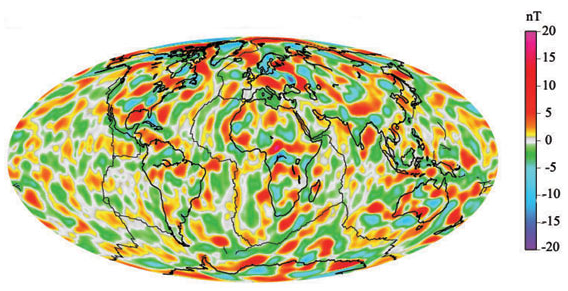

Researchers with the European Space Agency (ESA) are reporting that a peculiar oddity in the Earth’s magnetic field known as the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly is weakening faster than the rest of the planet’s magnetic field, and may well be showing signs of splitting into two distinct regions.

First discovered in 1958, the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly is an area where the Earth’s magnetic field is at its weakest. Stretching across the South Atlantic from Chile to Zimbabwe, the Anomaly allows the inner Van Allen radiation belt, a series of doughnut-shaped zones in the Earth’s magnetosphere that trap energetic charged particles emanating from the Sun, to dip to within 200 kilometers (120 miles) of the planet’s surface.

This phenomenon is caused by a particular asymmetry in the planet’s structure that causes the center of Earth’s magnetic field to be located in a different place than the planet’s physical center; instead, it is located somewhat north of the Earth’s physical center and slightly toward Singapore, resulting in the outer edge of the field dipping down toward the South Atlantic.

The Anomaly has also been changing over time, not only in shape and size but also in intensity: since the mid-nineteenth century, it has increased in size from 30 million km² to over 100 million km², and its average field strength has dropped by nearly 12 percent over that same time period.

This is more pronounced than the nine percent decrease in the overall strength of the Earth’s magnetic field over the past two centuries, and the shape of the Anomaly indicates that it might be in the process of splitting into two separate nodes. In response, the ESA has dispatched their fleet of three Swarm satellites to investigate these changes, in the hope that this magnetic oddity can offer new insights into how the Earth generates her magnetic field, and how that field changes over time.

Although the current weakening of the planet’s magnetic field could simply be a temporary fluctuation, drops in strength such as this are also known to precede geomagnetic reversals—the flipping of the Earth’s magnetic poles—and research has indicated that if this is the case then the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly could be the epicenter of this reversal.

The planet’s magnetic field is thought to be generated by differences in the flow of the planet’s outer core, being composed of mostly liquid iron and nickel. Heat from the solid inner core drives currents that have been observed in the outer core, and the Coriolis effect organizes these currents into regional zones that act like massive electrical generators; in turn, that electrical current generates a series of localized magnetic fields. Combined together, these individual fields form the larger effect known as the Earth’s magnetic field.

During geomagnetic reversals, these individual magnetic fields fall out of sync, resulting in a jumble of disparate regional fields that eventually re-align to form a cohesive one similar to the one that preceded it, although the field’s polarity is often flipped, with north becoming south and south taking the place of north.

The last such reversal took place 780,000 years ago, although these events follow no set schedule, with the geological record revealing past rapid-fire events that took place only 500 centuries apart, and much longer periods with 40 million years between reversals—statistically speaking, these events appear to occur entirely at random. The ESA researchers are hoping to glean new information from the South Atlantic Anomaly’s ongoing changes to learn how this process works, and perhaps to find a way to predict when a geomagnetic reversal might occur.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

Hmm, ‘Coriolis effect organizes these currents into regional zones that act like massive electrical generators; in turn, that electrical current generates a series of localized magnetic fields.’

Could this be used as a power source? Sounds like a potential worth investigating.

If this magnetic field could be tapped and directed it might prove to be a massive amount of energy.

But, maybe we should wait until the magnetic field stabilizes after the flip to start tapping into it…

It’s not a bad idea, but such a generator would only produce a minuscule amount of electricity, since Earth’s magnetic field is thousands of times weaker than the magnets used in traditional electrical generators, even hundreds of times weaker than a typical fridge magnet—and those are barely strong enough to hold up children’s artwork! 😉