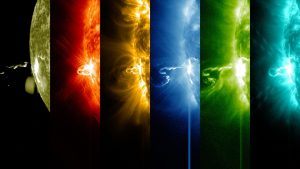

Officially kicking off in December of 2019, this solar cycle has defied predictions that it would be yet another mild one, having already seen a handful of X1-class solar flares; as an X2.2, the flare that occurred on April 20 was 2.2 times stronger than an X1 flare. Although the charged particles in the CME that came from this recent outburst weren’t aimed at Earth, the x-rays emitted from the flare itself caused a strong class-R3 radio blackout over the eastern half of the Eurasian continent and Australia.

This X2.2 flare is also the strongest flare seen since an X9 that was unleashed in September 2017; the strongest flare ever observed occurred in 2003, and was in excess of X28 in strength. For comparison, the flare that triggered an intense geomagnetic storm strong enough to catch telegraph wires on fire in 1859 known as the Carrington Event is estimated to have been an X45-class flare.

This recent flare comes from one of two large sunspot regions that appeared on the surface of the Sun a few days before the occurrence of the flare itself, with individual spots in these clusters measured as being larger than the Earth is wide; however, we’re still in the early days of solar cycle 25.

“I’m sure we shall see larger [active regions] over the next few years,” according to solar physicist Dean Pesnell of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “Active regions 2993 and 2994 are middling in size and don’t represent the best that Solar Cycle 25 can produce.”

We might have dodged this bullet, but we can’t be lucky forever: learn about the danger presented by these solar storms—and what needs to be done to weather them—in Whitley’s 2012 ebook Solar Flares: What You Need to Know.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.