Details of the Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials conducted on Russia’s controversial Sputnik V vaccine were released on September 4, nearly four weeks after Moscow’s approval of the yet-unproven COVID-19 inoculant. The paper, published in the medical journal The Lancet, confirmed that the vaccine, developed by Moscow’s Gamaleya Institute, had been tested on less than 100 volunteers before approval for civilian use was granted in early August, with Russian officials vouching for its safety and effectiveness, despite the vaccine not having run the gauntlet of its critical Phase-3 clinical trials, to determine if these claims were indeed true.

Details of the Phase 1 and 2 clinical trials conducted on Russia’s controversial Sputnik V vaccine were released on September 4, nearly four weeks after Moscow’s approval of the yet-unproven COVID-19 inoculant. The paper, published in the medical journal The Lancet, confirmed that the vaccine, developed by Moscow’s Gamaleya Institute, had been tested on less than 100 volunteers before approval for civilian use was granted in early August, with Russian officials vouching for its safety and effectiveness, despite the vaccine not having run the gauntlet of its critical Phase-3 clinical trials, to determine if these claims were indeed true.

The paper outlined the phase 1 and 2 studies that tested Sputnik V, consisting of “two open, non-randomised phase 1/2 studies at two hospitals in Russia,” according to the study text, with each trial consisting of 38 test subjects, for a total of 76 “healthy adult volunteers (men and women) aged 18–60 years.”

The paper reports that the vaccine appeared to be safely accepted by the volunteers’ bodies, and reported that “most adverse events were mild and no serious adverse events were detected.” These adverse effects were flu-like symptoms such as headache, rise in body temperature and lack of energy, symptoms that are common after the administering of a vaccine, as the body’s immune system responds to the newly-introduced stimulus.

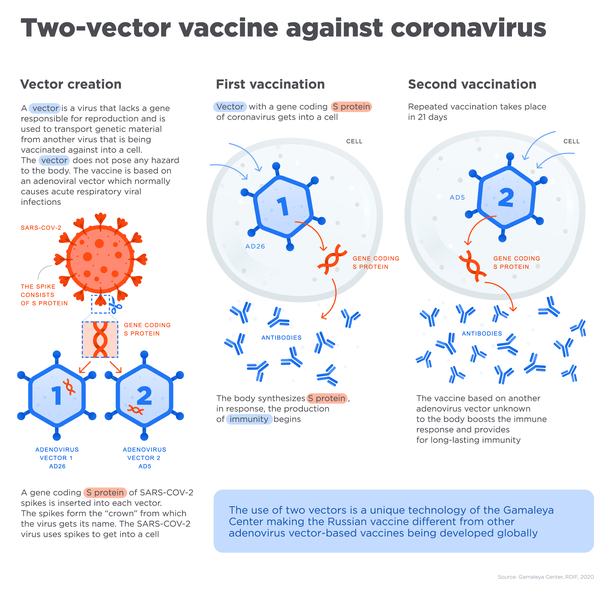

“All participants produced antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 glycoprotein,” the study found, meaning that the vaccine was effective in prompting an immune response that could be used to neutralize the coronavirus. Antibodies are Y-shaped protein molecules produced by the immune system that are keyed to either mark a specific bacterium or virus for attack by the immune system, or used to overwhelm the pathogen directly by smothering it in antibodies.

The paper reports that the number of antibodies produced were higher than that found in convalescent plasma, a vaccine-like treatment that uses blood plasma extracted from COVID-19 survivors that can be used to treat patients with the same illness. The paper also reports that the vaccine prompted a T-cell response, specialized “hunter/killer” cells that either directly or indirectly eliminate harmful pathogens, within the subjects’ immune systems.

The paper’s authors provided transparency in listing the numerous limitations that may have hampered the effectiveness of the studies, including the short 42-day duration for follow-up checks—it’s currently unknown if vaccine-prompted SARS-CoV-2 antibodies will last for any useful amount of time, as naturally-acquired antibodies fade from the body rather quickly. No placebo or control vaccine group was used in the study, to help weed out potential false positives, and the small group of 76 volunteers (100-300 subjects are typically required for a typical Phase 2 trial) was considered to be too small a sample to make an effective determination of Sputnik V’s overall safety or effectiveness.

The volunteers involved in the study were also not as diverse as the study authors had hoped. “Despite planning to recruit healthy volunteers aged 18–60 years, in general, our study included fairly young volunteers. Further research is needed to evaluate the vaccine in different populations, including older age groups, individuals with underlying medical conditions, and people in at-risk groups,” according to the study text.

Phase 3 clinical trials for Sputnik V only began in early August, and should involve tens of thousands of volunteers to confirm the vaccine’s efficacy (how effective the drug is under ideal conditions) and evaluate its effectiveness (how well it works under real-world circumstances), monitor side effects, and gather further data that will be used in the drug’s medical use—if approved.

But under normal circumstances roughly half of all candidate drugs wash out during their Phase 3 trials—typically even more in the case of vaccine candidates—and this phase is critical, since without wide-scale testing it is impossible to know if the vaccine is indeed safe, let alone effective against the coronavirus itself: an antibody-based immune response being observed in test subjects does not necessarily mean that the vaccine will be effective against the actual coronavirus, a factor that won’t be realized until inoculated individuals are exposed to the actual virus.

Subscribers, to watch the subscriber version of the video, first log in then click on Dreamland Subscriber-Only Video Podcast link.

SmartPhone news on September 17th reported 1 in 7 Russian vaccine recipients are having side effects. That may be more than expected.